22 Common Options Trading Terminology for beginners

Options trading comes with its own specialised terminology, which can initially seem overwhelming to beginners. However, mastering these key terms is crucial for anyone looking to trade options successfully and implement various strategies with confidence.

Options Trading Terminology For Beginners covers 22 fundamental options trading terminology concepts, including calls, puts, volatility, pricing models, options Greeks, and trading strategies.

Familiarity with options trading terminology enables traders to communicate effectively, refine their trading approach, and enhance profitability. Understanding these terms is essential for analysing options pricing, managing risks, and evaluating strategies, all of which contribute to long-term trading success.

The language of options trading includes critical concepts such as volatility, premium pricing, order types, potential profits, expiration effects, and trading techniques. Important terms include standard deviation, which measures price fluctuations of the underlying asset; exercise, which refers to converting contracts into assets; change, indicating daily premium variations; volume, representing the number of contracts traded; short, which means selling to open a position; volatility, reflecting market uncertainty; assignment, when an option holder is required to fulfil a contract; long, meaning the purchase of an options contract; bid price, showing buyer interest; and ask price, representing seller supply.

Other key terms include last traded price, reflecting recent transaction values; intrinsic value, denoting an option’s built-in profit; expiration date, marking when an option contract ends; strike price, defining the agreed-upon cost of execution; open interest, indicating the number of outstanding contracts; time value, representing the portion of an option’s price beyond intrinsic value; contract name, identifying the specific option; stop-loss order, a risk management tool to limit potential losses; in-the-money, meaning an option has intrinsic value; out-of-the-money, signifying no immediate profit; at-the-money, where the strike price and market price are equal; and the distinction between index options, which track entire markets, and equity options, which focus on individual stocks.

A solid understanding of these terms is vital for analysing market trends, choosing the right strategies, managing risks, and ultimately achieving success in options trading terminology.

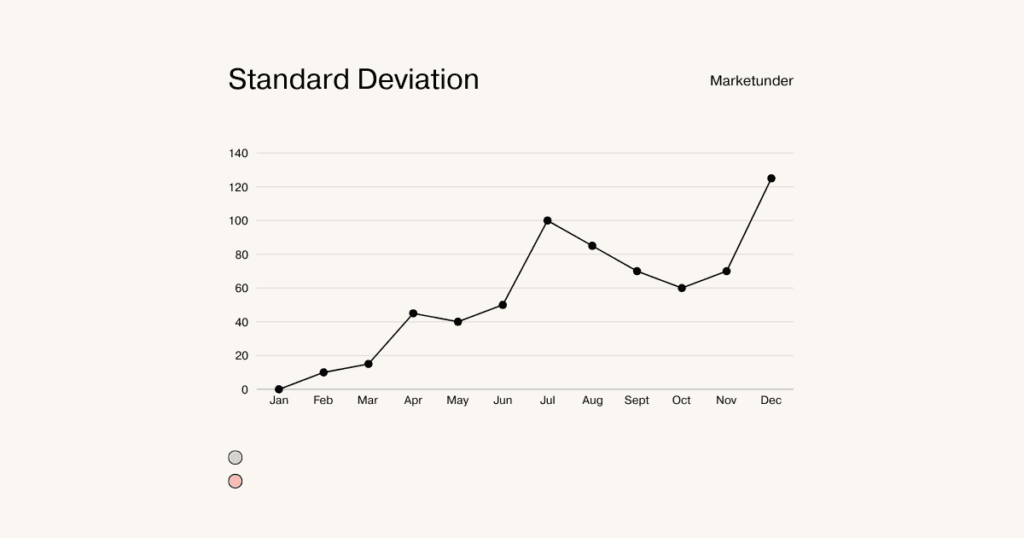

1. Standard Deviation

Standard deviation is a statistical measure that quantifies the dispersion of price returns from their mean, providing traders with a key indicator of volatility. It reflects how tightly or loosely price data clusters around the average, with a low standard deviation indicating that price movements are relatively stable, while a high standard deviation suggests greater fluctuation and unpredictability.

In options trading, standard deviation is primarily used to assess the annual volatility of an underlying asset. For example, if an asset has an annualised standard deviation of 25%, this implies that its price typically fluctuates within a 25% range above or below its mean return each year. Traders rely on this measure to evaluate an asset’s volatility and price movement tendencies, helping them refine their trading strategies.

Another key application of standard deviation is in forecasting potential price movements using historical volatility data. By incorporating standard deviation into probability models, traders can estimate the likelihood of various price outcomes. Statistically, prices tend to stay within a one standard deviation range (68% probability), two standard deviations (95% probability), or three standard deviations (99% probability) of the mean. This probabilistic approach allows traders to detect potential mispriced options, especially when implied volatility diverges significantly from historical volatility.

Comparing historical standard deviation with implied volatility is a common technique for identifying overpriced or underpriced options. Implied volatility, which is derived from an option’s price, represents the market’s expectation of future volatility. If implied volatility is higher than historical standard deviation, it often indicates that options are overpriced due to excessive volatility expectations. Conversely, if the historical standard deviation is greater than implied volatility, it may suggest that options are undervalued, presenting a potential buying opportunity.

This comparison forms the basis for volatility-based trading strategies and works in tandem with options Greeks, particularly Vega, which measures an option’s sensitivity to volatility changes. Traders can exploit volatility skews by adjusting their positions based on the deviation between implied and historical volatility.

Example: Sensex and Nifty Options Trading

Consider an example from the Sensex and Nifty index on the National Stock Exchange (NSE). Suppose historical data shows that the Nifty index has a standard deviation of 18% over the past three years, while 1-month Nifty call options are trading at an implied volatility of 22%. Since implied volatility exceeds the historical standard deviation, this suggests potential overvaluation of the options.

In such a scenario, a trader might deploy a volatility arbitrage strategy, selling the 1-month call options while hedging the position by buying longer-dated calls with lower implied volatility closer to historical norms. If implied volatility later declines toward historical levels, the trader could profit from the narrowing volatility gap.

Conversely, if the 1-month standard deviation were 25%, while implied volatility stood at 18%, it could indicate that options are undervalued. Here, a trader might take the opposite approach—buying short-term call options and selling longer-term calls, anticipating an increase in volatility that would drive up option prices.

By leveraging standard deviation alongside implied volatility, traders can make more informed decisions, improve risk management, and capitalise on market inefficiencies in the options market.

2. Exercise

Exercise is the process by which an option holder executes their right to buy or sell the underlying asset, effectively converting their options contract into an actual transaction. In the case of a call option, exercising means purchasing the asset at the strike price, often to capitalize on price differences in the market. For a put option, exercising involves selling the asset at the strike price to take advantage of a price drop.

When an option is exercised, the notional value of the contract turns into a real financial position—whether it’s stocks, futures, or indices—depending on the type of option. The option holder must notify their broker to exercise their right before or on the expiration date. Typically, traders only exercise options that are in the money, as this allows them to realize intrinsic value and lock in profits.

Why Exercise an Option?

Options are exercised when there’s an arbitrage opportunity due to the difference between the strike price and the market price of the underlying asset. For example, if a call option has a strike price of ₹100 while the stock trades at ₹110, exercising allows the trader to buy at ₹100 and sell at ₹110, earning ₹10 per share. Similarly, exercising a put optionwith a ₹100 strike price when the stock has dropped to ₹90 results in a ₹10 per share gain.

Most brokers automatically exercise in-the-money options at expiration to ensure clients don’t miss out on potential profits. However, out-of-the-money options expire worthless, meaning the trader loses only the premium paid for the option.

Assignment and Exercise Risks

For traders selling options, exercise leads to assignment, meaning they are obligated to fulfill the contract terms. A covered call seller faces assignment if the stock closes above the short call’s strike price, requiring them to sell their shares to the call buyer. Similarly, a covered put seller gets assigned if the stock falls below the short put strike, forcing them to buy shares at the agreed price.

Early Exercise in American-Style Options

Unlike European-style options, which can only be exercised at expiration, American-style options allow early exercise anytime before expiry. However, early exercise is rarely beneficial because an option typically retains extrinsic value, which is lost upon exercise. That said, early exercise can be advantageous in situations such as:

- Deep in-the-money options with minimal time value

- Upcoming dividend payments, where exercising a call ensures ownership before the ex-dividend date

- Corporate events like mergers, which may impact stock prices

Example: Exercising a Nifty Call Option

Suppose a trader buys a 1-month Nifty 50 call option with a strike price of 12,000, and at the time of purchase, the index trades at 11,800. As expiration nears, if the Nifty index rises to 12,100, the call option now has ₹100 of intrinsic value. The trader can exercise the option, buy Nifty futures at ₹12,000, and immediately sell at ₹12,100, locking in a risk-free profit of ₹100 per lot.

However, if Nifty drops to 11,600, the call expires worthless, and the trader does not exercise it since there is no intrinsic value. In this case, the loss is limited to the premium initially paid for the option.

By understanding how and when to exercise options, traders can maximise profits, avoid unnecessary risks, and optimise their trading strategies.

3. Change

The term “change” in options trading refers to the difference between an option’s current market price and its previous closing price. It reflects the daily fluctuation in option premiums, driven by factors such as market movements, trading volume, and broader economic events. A positive change indicates an increase in the option’s value, while a negative change signals a decline.

Essentially, change quantifies the rupee or percentage shift in an option’s price from one trading session to the next. Since option prices fluctuate continuously due to movements in the underlying asset, time decay, volatility, and market sentiment, the change metric helps traders gauge short-term trends and price momentum.

Why Change Matters in Options Trading

Traders monitor daily changes in option prices to identify potential opportunities and shifts in market dynamics. A sharp overnight increase in option premiums could signal heightened volatility, breaking news, or a trend reversal, while a steep decline might indicate a cooling-off period or profit-taking.

Understanding the context behind an option’s price change is crucial. Factors such as time to expiry, upcoming events, liquidity conditions, and demand-supply imbalances all influence price movements. A large intraday change can impact trading strategies, prompting traders to adjust positions, hedge risk, or capitalise on short-term pricing.

Using Change for Trading Strategies

- Exploiting High Positive Change: When an option experiences a significant upside change, traders might sell options at inflated premiums, taking advantage of temporary price spikes. Writing options at higher prices can be profitable if volatility normalises.

- Taking Advantage of Downside Change: If an option’s price drops sharply, it may present a buying opportunity for long positions. Traders might purchase calls or puts at discounted prices, anticipating a rebound.

- Hedging and Rollover Decisions: A significant downside change near expiration could suggest early unwinding of short positions to lock in profits, while an upside change may encourage rolling over to longer-dated contracts to maintain exposure to an ongoing trend.

Example: Bank Nifty Put Option

Consider a Bank Nifty put option set to expire in 10 days, currently trading at ₹150. Overnight, negative market sentiment leads to a 3% drop in the Bank Nifty index, causing a surge in demand for put options. As a result, the next day, the put premium jumps by ₹50, opening at ₹200—a 33% upside change.

This sharp increase in premium presents an opportunity for traders to sell puts at elevated prices. A trader might short the put at ₹200, expecting volatility to subside and the option’s price to revert closer to its original ₹150 level before expiry. By capitalizing on this temporary surge, the trader can potentially profit as the market stabilizes.

By analysing daily changes in option premiums, traders can refine their strategies, make better entry and exit decisions, and optimise their risk management approach in volatile market conditions.

4. Volume

Trading volume refers to the total number of options contracts exchanged over a specified period. It reflects the overall quantity of contracts bought and sold by market participants for a particular strike price or expiration date. Volume serves as an indicator of liquidity, which is the ease with which traders can enter and exit positions. Options with higher trading volume typically have narrower bid-ask spreads and can be traded in large quantities without significant price fluctuations or slippage.

Intraday volume data tracks trading activity at specific intervals throughout the day, while daily or monthly volume aggregates the total number of contracts exchanged within those respective time frames. Analyzing volume helps reveal the level of market interest, providing insights into buying and selling pressure.

Volume analysis is vital for evaluating liquidity, determining market sentiment, and making informed decisions about trade sizes. Active options with large volumes offer greater flexibility, allowing traders to swiftly enter and exit trades without causing significant price changes. In contrast, low-volume contracts should be traded in smaller quantities to minimize slippage risks.

Sudden increases in options volume can indicate heightened activity, often signaling a strong directional movement or the onset of a volatility event. Such volume spikes also help confirm breakouts and detect potential reversals in technical analysis.

Traders often examine the option chain— a matrix displaying available strikes and expiration dates— to identify high-volume options that might present promising trade opportunities. The most active options tend to reflect market consensus and attract enough interest to ensure better trade executions. Volume data also aids in strategic decisions like block trades, risk reversals, and volatility arbitrage, all of which benefit from high liquidity.

Take, for example, the daily options volume for the Nifty Index on the National Stock Exchange around significant events:

- Regular day: 100,000 Nifty 10000 call contracts traded

- Pre-earnings: 300,000 Nifty 10000 call contracts traded

- Budget day: 500,000 Nifty 10000 call contracts traded

The surge in volume during such times highlights increased trader participation and a potential directional bias, especially if traders anticipate a rise in Nifty. Arbitrageurs, taking advantage of the heightened liquidity and high implied volatility, might sell these calls to profit from the subsequent volatility contraction after the event.

5. Short

The term ‘short’ refers to selling options contracts to initiate a new position, as opposed to buying to open. When traders engage in short selling of options, they take on the responsibility of fulfilling the contract’s terms if assigned by the counterparty. Short sellers collect premiums upfront by selling options, but they face potential risk if the market moves unfavorably.

For those shorting call options, the obligation is to deliver the underlying asset at the strike price if the option is exercised at expiration. In the case of short put options, the seller must purchase the underlying asset at the strike price if the buyer exercises the put at expiration. Short positions typically benefit from time decay, as the value of options tends to decrease as expiration nears.

Traders use short options as a strategy when expecting minimal market movement, as they can collect premiums with relatively low risk. The premium collected acts as a cushion in case of slight declines in the underlying asset, while providing potential profits if the price remains range-bound. However, short positions must be covered, typically by holding the underlying asset, to avoid the risk of unlimited losses.

Short options can also serve as hedging tools to mitigate risks from other investments. For instance, owning stock exposes the trader to downside risk, which can be offset by shorting calls against the stock. Shorting can also generate income that helps reduce the cost of holding a long position.

Common short options strategies include naked and covered writing, bear spreads, ratio spreads, and volatility arbitrage. Naked shorts carry higher risks and margin requirements, while covered shorts are often used on assets like stocks or futures to boost income. Spreads combine short and long options to limit risk, and arbitrageurs typically short overvalued options while hedging the position.

For example, a cautious options trader on Reliance Industries might sell a 1500 put and a 2000 call for a one-month strangle, hoping for sideways or minimal price movement. The short positions generate premium income, with potential profits if the price remains between the two strikes at expiration. The trade is hedged by maintaining sufficient margin to cover potential assignment risks on both sides.

6. Volatility

Volatility measures the extent and frequency of price fluctuations in an underlying asset over a certain period. It indicates how likely the price is to experience significant upward or downward movements. Higher volatility suggests larger daily price swings, often with frequent reversals, while lower volatility indicates more stable price behaviour with narrow fluctuations.

Volatility plays a central role in determining the premiums of options contracts. As volatility increases, options tend to become more valuable because the likelihood of significant price movements grows. Essentially, volatility quantifies the level of uncertainty embedded in options pricing.

Traders often look at volatility indicators like historical volatility and implied volatility to gauge the potential price range of the underlying asset. The volatility level reveals how spread out possible price movements might be. When volatility is high, the potential outcomes are broader, which makes options more valuable to buyers. By analyzing volatility, traders can assess whether options are underpriced or overpriced based on current volatility trends, enabling them to profit by buying undervalued options or selling overvalued ones.

Volatility analysis is widely used across various strategies, including forecasting, volatility trading, risk management, and structuring options spreads. Traders adopt either long or short volatility strategies to benefit from expanding or contracting volatility. Additionally, options can be used as hedges to protect portfolios, with those that increase in value as volatility rises providing a cushion against market risks.

Crude oil often experiences sharp price swings and increased volatility during key events like supply disruptions or OPEC meetings. Traders can take advantage of these fluctuations by utilizing options that benefit from volatility spikes. For example, buying crude oil call options with low volatility before an expected surge in volatility can lead to gains as the uncertainty heightens. Crude oil, with its cyclical volatility, offers frequent opportunities for volatility-based trades.

7. Assignment

Assignment refers to the process by which the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC) distributes exercised options contracts to the corresponding sellers to full fill their obligations. When an option holder exercises their right, the OCC randomly assigns the contract to an active seller, who must then take the necessary actions to complete the settlement.

For call options, assignment obligates the seller to deliver the underlying asset to the buyer. The seller must transfer the asset to the OCC, which in turn provides it to the call option holder. With put options, assignment requires the seller to immediately purchase the underlying asset from the exercising put holder at the strike price.

Assignment typically occurs when in-the-money options are exercised close to expiration. The OCC allocates these contracts randomly to active sellers, creating a responsibility for them to fulfill the required settlement. In the case of call options, the seller must deliver the underlying asset to the OCC, while put sellers must purchase it.

This system ensures that the settlement process runs smoothly when options are exercised for a profit. By assigning contracts to sellers, the OCC helps convert options into either the underlying asset or a cash settlement for the holder at expiration.

Sellers of both naked and covered options face assignment risk. For covered calls, the seller risks having to forfeit the underlying asset if assigned. On the other hand, covered put sellers may have to buy additional stock if their puts are exercised. Naked call and put sellers carry significant risks, as there’s no cap on potential losses if their open positions are exercised.

Consider a trader who sells Nifty put options with a 12,000 strike price while the index is at 12,500. If, at expiration, the Nifty falls to 11,800 and the 12,000 puts are exercised, the trader will face assignment risk. The OCC will randomly assign the exercised puts to active sellers, and the trader must buy Nifty at Rs. 12,000, incurring a loss of Rs. 200 per lot. Understanding assignment mechanics and planning exit strategies around expiration is crucial for sellers of short options.

8. Long

In options trading, going long refers to purchasing or holding a call or put option, with the expectation that the underlying asset’s price will move in a favourable direction before the option expires. A long position benefits when the option’s premium increases, allowing the trader to sell the option at a higher price than the initial purchase.

It’s crucial to understand that options are sophisticated financial tools, best suited for experienced investors who are fully aware of the risks they carry.

Traders evaluate factors such as implied volatility, time to expiration, strike price selection, and liquidity to identify optimal entry points. Actively managing long positions involves adjusting strikes or rolling over contracts to capitalize on ongoing momentum.

For instance, a trader may buy Infosys call options if they anticipate strong IT spending and positive movement ahead of the company’s quarterly earnings report. If the actual announcement surpasses expectations and Infosys’ stock price rises, the call options will become more valuable. The trader can then sell the calls at higher premiums to lock in profits.

9. Bid

The bid price is the highest amount a buyer is willing to pay for an options contract. It is an essential element, along with the ask price, in determining live quotes within the options market. The bid reflects the maximum price a buyer is prepared to pay at that moment to open a long position in either a call or put option. It helps establish the demand side of the pricing dynamic between potential buyers and sellers of a specific options contract.

On exchanges such as NSE or BSE, the bid is the highest pending order from a buyer, marking the best potential price for sellers looking to initiate new short positions. Active options traders track the levels of bids relative to market prices and ask quotes. An increasing bid suggests stronger buyer interest, particularly when it rises compared to the last transaction price, while falling bid levels indicate diminishing demand.

Changes in the bid price result from fluctuating supply and demand conditions, as well as shifting market expectations. Buyers might raise their bids if they expect favorable movements in the underlying asset before the option’s expiration, whereas bids will drop if buyers are less willing to pay high premiums due to a pessimistic outlook.

Traders use strategies based on bid prices, seeking to make purchases when the bid is at or below its fair value as estimated by pricing models. For better entry chances, they might start by placing a lower bid, then gradually increase it if necessary. Patience is key to securing favorable entries, and traders may lift their bids when volatility decreases or positive news emerges. It’s generally wise to avoid chasing ask prices higher unless there’s a strong bullish outlook—letting sellers make the first move instead.

For example, if the bid-ask quote for Reliance 2400 call options is Rs 75 – Rs 80, a trader might place a bid of Rs 77 to improve their chances of entering a long call position at a more attractive price. The order would be filled if a seller accepts Rs 77 or lowers their ask to match the bid.

10. Ask

The ask price, or offer price, represents the lowest price at which a seller is willing to part with an options contract. It works in tandem with the bid price and is fundamental to options trading.

When an investor seeks to sell an options contract, they determine their minimum acceptable price, which is their ask. For example, if HDFC Bank shares are priced at Rs 1,500, an investor may ask for Rs 125 to sell a call option on HDFC Bank at a strike price of Rs 1,600 with a two-month expiration. This indicates the seller will only sell the option if they receive at least Rs 125, as compensation for taking on the risk of potentially having to sell the underlying shares.

A higher ask price signals that the seller requires a larger return to take on the risk of the trade. For call options, a higher ask often indicates that the seller believes the underlying asset is unlikely to experience a significant price rise. For puts, a higher ask suggests the seller does not anticipate a major drop in the asset’s price.

The seller’s goal is to set the ask price high enough to ensure a profit, but not so high that no buyer is willing to purchase the option. As the option nears expiration, the seller may reduce the ask price, given less time for the underlying price to move in their favor. Implied volatility plays a significant role here; higher volatility makes larger price movements more likely, which justifies a higher ask price.

A typical strategy for sellers is to start with a high ask and then gradually lower it until a buyer is willing to meet it. This enables the seller to capture the highest possible premium while still selling the option within a reasonable time frame.

The bid and ask process helps establish the market price of an option. On electronic platforms such as those offered by the NSE and BSE, the ask price represents the lowest price a seller is willing to accept for an option contract. A trade occurs when a buyer’s bid matches or exceeds this ask price.

For instance, a trader might ask for Rs 75 to sell an Infosys Rs 1,400 put option with a six-month expiration. If a buyer bids Rs 80, the trade is executed at Rs 80, with the seller receiving the premium and taking on the obligation to buy Infosys shares at Rs 1,400, should the option be exercised.

11. Last

The last price is the most recent price at which an options contract was traded. It updates in real-time as buy and sell orders are matched. Along with bid, ask, and volume data, the last price is a critical indicator for options traders, reflecting the most recent transaction agreed upon by a buyer and a seller.

The last price fluctuates frequently during trading hours as market expectations evolve. For highly liquid options on popular stocks or indices, the last price may change multiple times per minute. In contrast, less liquid options may see infrequent updates.

Traders carefully monitor the last price in relation to current bid and ask prices to assess the sentiment of buyers and sellers. If the last price is lower than the ask price, it suggests the seller has reduced their price to find a buyer. Conversely, if the last price exceeds the bid, it indicates that buyers were willing to pay more than the current bid.

The last price also serves as a useful reference for evaluating an option’s theoretical value. If the last price significantly exceeds the estimated value based on pricing models, the option may be overvalued. Conversely, if it’s well below theoretical value, it could present a buying opportunity.

Lastly, the last price is essential for tracking the performance of an options position. Traders can calculate unrealized profit or loss by comparing the entry price to the current last price, and this ongoing update provides valuable insight into how a trade is progressing.

For example, a trader may have bought an ICICI Bank Rs 500 call option at Rs 35. If the last price rises to Rs 60 due to a rally in ICICI shares, the trader would have an unrealized profit of Rs 25 per option. The trader can either hold the option for further gains or sell it to lock in the profit.

12. Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value refers to the inherent value of an option based on its current strike price and the market price of the underlying asset. It represents the portion of an option’s premium that is unaffected by time decay. For in-the-money options, intrinsic value establishes a minimum value, essentially acting as a price floor.

The intrinsic value of an option represents its real worth based on the difference between the strike price and the market price of the underlying asset. For call options, intrinsic value is the amount by which the market price of the underlying asset exceeds the strike price. Conversely, for put options, it is the amount by which the strike price is higher than the current market price. Only in-the-money options have intrinsic value, while at-the-money and out-of-the-money options have none.

For example, suppose a trader holds a Wipro call option with a strike price of ₹500 while Wipro’s stock is trading at ₹550. The intrinsic value of this option is ₹50 per share because the right to buy Wipro at ₹500 holds an immediate gain of ₹50 when the stock can be sold at ₹550. If Wipro’s price drops to ₹450, the call option loses its intrinsic value entirely.

Intrinsic value acts as the baseline for an option’s price, with the remaining portion of the premium attributed to time value, also known as extrinsic value. Deep in-the-money options derive most of their premium from intrinsic value, whereas at-the-money and out-of-the-money options primarily reflect time value.

Traders calculate intrinsic value to distinguish between the fundamental worth of an option and the speculative premium based on market expectations. Comparing an option’s intrinsic value to its total market price helps identify potential mispricing, aiding traders in making informed decisions. Understanding how intrinsic and extrinsic values contribute to an option’s price is essential for effective trading strategies.

Monitoring intrinsic value becomes particularly important as an option nears expiration. Since time value erodes over time, intrinsic value plays a larger role in determining the final premium. By expiration day, time value diminishes to zero, leaving only intrinsic value for in-the-money options. This factor is crucial when making final trading or exercise decisions.

For advanced strategies such as spreads, intrinsic value is key in determining potential profit. The maximum gain in a spread strategy is often the difference between the intrinsic values of the long and short positions. Therefore, estimating intrinsic value provides valuable insight into the strategy’s profit potential.

When trading options on stocks like Reliance, Infosys, or Tata Motors, intrinsic value serves as a crucial metric. For instance, if a trader holds Tata Motors ₹400 put options while the stock trades at ₹380, the puts carry ₹20 of intrinsic value per share. This intrinsic component remains constant regardless of fluctuations in time value, ensuring a minimum level of worth for the option.

13. Expiration Date

The expiration date is the final day on which an options contract remains valid. Until this date, the option holder retains the right to exercise the contract as per its terms. However, once the expiration date passes, the contract becomes worthless, and all associated rights and obligations are nullified.

Options contracts come with a predetermined expiration cycle, which is established by the exchange on which they are listed. For instance, stock options on the National Stock Exchange of India (NSE) typically follow a monthly expiration cycle, whereas index options expire on the last Thursday of the contract month. In U.S. markets, options generally expire on the third Friday of each month.

The time remaining until expiration significantly influences an option’s pricing and value. Options with a longer duration retain more time value, as they have a greater probability of becoming profitable before expiration. This time value component, also known as extrinsic value, decreases as expiration nears. Options that are set to expire soon tend to have minimal or no time value left.

As the expiration date draws closer, time value diminishes at an accelerating rate—a phenomenon known as theta decay. This decline in extrinsic value becomes particularly steep in the final month of the contract. Traders keep a close eye on expiration timelines, making strategic decisions based on their market expectations. Approaching expiration, they typically consider the following options:

- Exercising a call option to buy shares if the stock price surpasses the strike price.

- Exercising a put option to sell shares at a favourable price if the stock falls below the strike price.

- Selling the option before expiration to capture any remaining time value.

- Letting the option expire worthless if it is out of the money.

- Rolling over the position by closing the current contract and opening a new one with a later expiration date.

- Using spread strategies to hedge exposure as expiration nears.

Expiration dates create a sense of urgency in options trading, as each contract has a fixed lifespan that ends definitively on a set date. Traders must manage their positions effectively, aiming to maximize gains or mitigate losses before the option expires.

For example, consider a trader in India who buys a one-month Reliance ₹2,000 call option on January 1st, with expiration set for January 31st. If Reliance stock climbs to ₹2,100 by January 15th, the trader might choose to exercise the option early, locking in a ₹100 per share profit. However, if the stock price falls to ₹1,900 by January 30th, the option will likely expire worthless the following day.

14. Strike Price

The strike price, also called the exercise price, is the predetermined price at which an option holder can buy or sell the underlying asset. This price is set when the contract is created and remains unchanged throughout its lifespan. For call options, the strike price represents the price at which the option holder can purchase the asset, while for put options, it is the price at which they can sell it. Since the strike price directly determines the profitability of an options contract, it plays a crucial role in trading decisions.

Strike prices are determined at fixed intervals relative to the current market price of the underlying asset. These intervals commonly include ₹1, ₹2.50, ₹5, and ₹10, depending on the stock and exchange rules. The strike price closest to the market price is referred to as “at-the-money.” Call options with strike prices below the market price are considered “in-the-money,” while put options with strike prices above the market price also fall into this category. Conversely, strike prices above the current stock price for calls and below for puts are categorized as “out-of-the-money.”

When selecting an option, traders evaluate various factors, including their risk appetite, price predictions, and breakeven levels. Additionally, they analyze how elements such as volatility, time to expiration, and interest rates influence an option’s potential profitability at a given strike price.

The relationship between an option’s strike price and the underlying asset’s market price plays a significant role in option pricing models. Deep in-the-money or deep out-of-the-money options tend to have higher extrinsic value due to volatility, whereas at-the-money options derive most of their worth from intrinsic value.

As expiration nears, the strike price becomes increasingly critical. Holders of in-the-money options must decide whether to exercise their contracts if the stock price moves favorably beyond the strike level. Out-of-the-money options, however, will expire worthless unless the market price shifts in their favor before expiration.

Traders use different strategies to select strike prices based on market conditions and risk management. A long straddle strategy, for instance, involves purchasing both a call and a put at the same at-the-money strike, aiming to profit from significant price swings in either direction. Spread strategies, on the other hand, involve holding multiple options with varying strike prices to control risk while defining maximum potential profits and losses. Strike price selection is essential when trading options on indices, stocks, and currencies, ensuring they align with expected market movements.

For example, a trader bullish on HDFC Bank might purchase a slightly out-of-the-money ₹1,500 call option when the stock is trading at ₹1,450, anticipating a rise beyond ₹1,500. Similarly, an investor expecting the Indian Rupee to weaken against the U.S. dollar could buy a USD/INR put option with a ₹75 strike price, betting that the rupee will drop below its current ₹74 exchange rate.

15. Open Interest

Open interest represents the total number of outstanding derivative contracts, including options, that remain active at the close of each trading day. It serves as a key indicator of market liquidity and participation. Open interest applies to both call and put options on a given underlying asset and is tracked daily by exchanges.

Each contract’s open interest reflects how many traders currently hold open positions that have not yet been closed, offset, or expired. High open interest generally signals strong market activity and liquidity, making it easier for traders to enter and exit positions.

As options trading unfolds throughout the session, open interest fluctuates based on the creation of new contracts and the closing of existing ones. When traders initiate fresh positions, open interest rises, indicating increased market participation. Conversely, when traders exit or offset their positions, open interest declines, reflecting a reduction in active contracts.

Options traders examine open interest trends to assess market sentiment and engagement. A rising open interest during an uptrend suggests that new buyers are entering call positions, anticipating further price appreciation. On the other hand, declining open interest during a downtrend often indicates that put holders are either taking profits or unwinding their positions due to a shift in sentiment.

The interaction between open interest, trading volume, and price movements offers valuable insights into market activity. For instance, when both open interest and volume increase simultaneously, it signals strong participation and fresh capital entering the market. In contrast, a decline in both metrics suggests that traders are closing positions and adopting a wait-and-see approach. Many traders also monitor open interest closely as expiration nears.

As an option approaches its expiration date, open interest in front-month contracts typically declines sharply, reflecting traders closing out positions to avoid assignment or losses. Meanwhile, an increase in open interest in longer-dated contracts suggests that traders are rolling over positions, preparing for extended market moves.

For example, suppose Infosys options currently have an open interest of 50,000 contracts across various strikes. If, on Monday, traders buy 5,000 new call options while only 1,000 put contracts are closed, the net change of 4,000 new contracts will push Tuesday’s open interest up to 54,000.

Market participants closely track open interest in major index and stock options, such as Nifty, Reliance, HDFC Bank, and TCS, to gauge shifts in sentiment. An increase in open interest in out-of-the-money Nifty call options, for instance, often reflects growing optimism that the index could break out to new highs.

16. Time Value

Time value, also known as extrinsic value, represents the portion of an option’s premium that accounts for the time remaining until expiration. It reflects the additional price a trader is willing to pay beyond an option’s intrinsic value, based on the probability that market fluctuations will push the option into profitability before it expires.

Intrinsic value applies only to in-the-money options, whereas all options possess some degree of time value, which is factored into their premium. As an option nears expiration, its time value steadily declines, a process known as time decay. Deep out-of-the-money options rely almost entirely on time value, as they lack any intrinsic worth.

Several factors influence an option’s time value, including the underlying asset’s price, strike price, time until expiration, market volatility, interest rates, and dividend payouts. Pricing models such as Black-Scholes use these variables to estimate an option’s theoretical time value. Generally, options with longer durations and those tied to highly volatile assets carry higher time value premiums.

Traders pay close attention to time value when assessing potential trades. If an option appears overpriced due to excessive time value, it may present an unfavorable risk-reward scenario. On the other hand, options with relatively low time value can provide strategic entry points ahead of expected market movements.

Active traders also track time decay closely, as it accelerates in the final weeks before expiration, significantly impacting option pricing and potential profits. The rate of time value erosion varies by strike price, influencing different trading strategies. For instance, covered call writing involves selling options to collect time value premiums, while rolling options to later expirations helps retain some remaining time value. Spread strategies also take time value differences between contract legs into account to optimize risk and reward.

For example, suppose a trader in India purchases a one-month out-of-the-money Nifty put option for ₹30. Since the option lacks intrinsic value, this ₹30 consists entirely of time value. If Nifty remains flat, the put option will lose value as expiration approaches, eventually decaying to zero as time value erodes.

17. Contract Name

A contract name is a standardized identifier assigned to an options contract, allowing traders to quickly recognize its specifications on an exchange. Understanding how contract names are structured is essential for navigating the options market efficiently. These names include key details such as the underlying asset, expiration date, option type (call or put), and strike price.

Options contract names follow standardized formats across exchanges, typically structured as:

Company ticker symbol + expiration month/date + call/put indicator + strike price

or

Underlying asset/index + expiration month + year + call/put + strike price

For instance, a contract labeled “RELIANCE Jan23 1900 Call” refers to a Reliance call option with a ₹1,900 strike price, expiring in January 2023. Similarly, “NIFTY 01Mar2024 15000 PE” represents a put option on the Nifty 50 index with a 15,000 strike price, expiring on March 1, 2024.

Traders quickly scan contract names in option chains to analyze pricing trends, expiration timelines, and strike price relevance. Small variations in contract names, such as different expiration dates or strike prices, distinguish unique trading instruments. Filtering options by familiar name patterns helps traders compare similar contracts efficiently.

Exchanges like NSE and BSE in India define strict naming conventions and provide detailed contract specifications to ensure transparency and uniformity. Traders also rely on advanced options platforms that aggregate contract names alongside key data, including volume, open interest, and bid-ask spreads.

Since selecting the wrong contract can lead to unintended trades, verifying contract names before executing orders is crucial. Ensuring accuracy in the contract’s underlying asset, expiration date, and strike price helps traders avoid costly mistakes.

18. Stop-Loss Order

A stop-loss order is a risk management tool that helps options traders limit potential losses by automatically closing a position when the price reaches a predefined level. This technique is particularly useful in volatile markets, as it provides a structured exit strategy to prevent excessive losses if a trade moves against expectations.

Stop-loss orders allow traders to set clear risk thresholds, ensuring disciplined decision-making and protecting capital from unpredictable price swings. These orders are especially valuable when trading options on high-volatility stocks or during uncertain market conditions, where sudden price fluctuations can quickly erode an option’s value.

For options buyers, a stop-loss order is typically executed using a stop-limit sell order placed below the option’s current market price. If the ask price drops to the stop level, the order activates, triggering a market sell order to close the position. Conversely, options sellers can place a stop-buy order above the option’s prevailing bid price to limit losses if the contract’s value surges unexpectedly.

Traders commonly set stop levels below the initial purchase price or above the original sale price to either secure partial profits or cap potential losses. A wider stop allows for natural price fluctuations, reducing premature exits, while a tighter stop ensures faster trade closures if adverse price action occurs. In fast-moving markets, stop-loss orders are particularly beneficial for traders handling multiple open positions across various assets, as they help manage risk and free up capital for better opportunities.

However, extreme market volatility can cause price gaps beyond the stop level before the order executes, leading to slippage. To mitigate this risk, traders often use stop-limit orders, which trigger only within a specified price range. Another effective risk management tool is the trailing stop, which adjusts dynamically with favorable price movements to lock in gains.

For example, suppose an Indian trader purchases Infosys ₹1,500 call options at ₹50 per contract. To limit potential losses to ₹20 per contract, they place a stop-sell order at ₹30. If the call options decline to ₹30, the stop order is activated, automatically closing the position and preventing further losses beyond the predefined ₹20 threshold.

19. In-The-Money (ITM) Options

An options contract is considered in-the-money (ITM) when it has intrinsic value, meaning the strike price is favorable compared to the current market price of the underlying asset. A call option is ITM if its strike price is lower than the market price, while a put option is ITM when its strike price is higher than the market price.

ITM options provide a built-in profit margin, calculated as the difference between the strike price and the prevailing market price. Exercising an ITM option before expiration allows traders to capture this intrinsic value immediately.

For instance, consider a Reliance ₹2,000 call option when Reliance stock is trading at ₹2,050. This option is ₹50 ITMsince it grants the right to buy shares at ₹2,000, which can immediately be sold for ₹2,050. Similarly, a Reliance ₹1,950 put option is also ₹50 ITM, as it allows selling shares at ₹1,950 when the market price is ₹2,000.

The deeper an option moves in the money, the higher its intrinsic value. However, its time value component also increases up to a certain point, reflecting the probability of further price movements. Deep ITM options are primarily composed of intrinsic value rather than time value, making them attractive for traders seeking lower risk.

Traders often choose ITM options that are 5–10% in the money, as they offer better risk-reward trade-offs compared to at-the-money (ATM) options. However, profit potential is capped beyond the strike price. Rolling ITM options to later expirations allows traders to maintain their exposure while benefiting from ongoing trends.

Another strategy involves using ITM options as a stock substitute to gain leveraged exposure without tying up large capital amounts. Losses are limited to the premium paid, while potential gains can be substantial if the stock continues moving favorably. Portfolio margin accounts can further enhance leverage for experienced traders.

For example, instead of investing ₹2 lakh in Infosys shares, a trader could purchase Infosys calls 5% ITM for half the capital, achieving similar upside potential with lower capital commitment. The option’s intrinsic value at the time of purchase helps mitigate premium risk.

20. Out-Of-The-Money (OTM) Options

An options contract is out-of-the-money (OTM) when it lacks intrinsic value because its strike price is unfavorable relative to the market price. OTM options derive their entire worth from time value, as there is no immediate profit if exercised.

For call options, OTM means the strike price is higher than the underlying asset’s market price. For put options, OTM means the strike price is lower than the market price. Since OTM options have no built-in value, they are priced solely based on the probability that they might become profitable before expiration.

Traders buy OTM options when expecting significant price movements that could push the contract into the money. The more extreme the OTM strike, the lower the premium but the greater the required price move for profitability. Moderately OTM options offer better leverage and a higher probability of success compared to far OTM alternatives.

During periods of high volatility, OTM options can yield outsized gains, making them popular for speculative trades. Since the maximum risk is limited to the premium paid, they provide leveraged exposure without the need for a large capital outlay.

Selling or writing OTM options is a common income-generating strategy. Since these options start out of the money, the probability of them expiring worthless is relatively high, reducing the likelihood of assignment. Covered call writing and cash-secured puts are popular strategies involving OTM options.

Traders also use OTM options for event-driven trades, such as earnings reports, economic policy changes, or major market events. For example, buying far OTM Nifty call options before an anticipated market rally offers low-cost upside exposure while capping potential losses to the premium paid.

21. At-The-Money (ATM) Options

An options contract is classified as at-the-money (ATM) when its strike price is approximately equal to the market price of the underlying asset. ATM options contain little to no intrinsic value and derive most of their worth from time value.

A call option is ATM when the strike price is near the current market price of the underlying asset, and the same applies to put options. Because ATM options sit at the threshold of profitability, they are highly sensitive to price movements.

ATM options are widely traded due to their balanced risk-reward profile. Their delta, which measures price sensitivity, is close to 0.50, meaning they have an equal chance of moving ITM or OTM. This characteristic makes them attractive for traders seeking directional exposure.

ATM options also have the highest time value, benefiting from volatility-driven price changes. Since liquidity is typically concentrated near the money, they offer tight bid-ask spreads and efficient order execution.

Traders favor ATM options for strategies requiring responsiveness to market shifts. Straddles, strangles, and butterfly spreads often use ATM options to maximize time value capture.

For instance, a trader expecting a major price swing in Reliance Industries might buy ATM call and put options as part of a straddle. If the stock moves significantly in either direction, one option becomes profitable while the other expires worthless, allowing the trader to capitalise on volatility.

22. Index Options vs. Equity Options

Options traders can choose between index options, which track broad market indices, and equity options, which are tied to individual stocks. Both offer leveraged exposure but serve different trading objectives.

Index options derive their value from market benchmarks like Nifty 50 or Bank Nifty, making them suitable for macroeconomic speculation or portfolio hedging. Their diversified nature reduces company-specific risk. Traders use index options to position for economic trends, geopolitical events, or interest rate changes.

Equity options, on the other hand, track individual stocks such as Reliance, Infosys, or HDFC Bank. These options react to company-specific events, including earnings reports, product launches, and corporate actions. Since single stocks can be more volatile than indices, equity options offer greater potential for rapid price swings but also carry higher risk.

Liquidity and trading volume are generally higher in index options, leading to lower bid-ask spreads and more efficient execution. Conversely, some individual stock options, particularly in smaller-cap stocks, may have wider spreads and lower liquidity.

Index options are often used for broad market exposure, while equity options cater to stock-specific trading strategies.

For example, a trader anticipating a strong economic recovery might buy Nifty 50 call options instead of selecting individual stocks. Meanwhile, another trader betting on Reliance’s growth might choose Reliance call options to capitalise on company-specific strength.

What is Options Trading?

Options trading is a financial strategy that involves buying and selling contracts tied to an underlying asset such as stocks, indices, commodities, or currencies. These contracts grant the buyer the right—but not the obligation—to purchase or sell the underlying asset at a predetermined price (strike price) before or on a specified expiration date. The seller of the contract, however, is obligated to fulfill the transaction if the buyer exercises the option.

Options are primarily divided into two categories: call options and put options. A call option gives its holder the right to buy the underlying asset, while a put option grants the right to sell it. Traders engage in options trading to speculate on price movements or hedge against market risks.

Options are traded on major exchanges such as the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) and through online brokerage platforms. However, before participating, investors must obtain approval from their broker, usually by completing an options trading agreement. Since options trading involves significant risk, it is not suitable for all investors. Beginners must thoroughly research, understand market dynamics, and assess their risk tolerance before diving in.

How Does Options Trading Work?

Options trading functions by allowing investors to buy or sell contracts based on the movement of an underlying asset. Each contract specifies key details such as:

- Type of option (Call or Put)

- Strike price (the agreed-upon price to buy or sell)

- Expiration date (when the contract expires)

- Premium (the price paid by the buyer to the seller for the contract)

- Contract size (typically representing 100 shares per contract in stock options)

Buyers of call options profit when the asset’s price rises above the strike price, while put option buyers gain when the price falls below the strike price. These traders can either sell their contracts for a profit or exercise the option.

Sellers, on the other hand, collect premiums in exchange for taking on the obligation to fulfill the contract. Their profit potential is limited to the premium received, and they can incur losses if the contract moves in favor of the buyer.

To trade options, investors must place an order through their brokerage account, selecting key parameters such as the asset, expiration date, strike price, and contract quantity. The trade is then executed on an exchange, where existing buyers and sellers match orders based on market conditions.

Since options are time-sensitive, traders must continuously monitor their positions. They can choose to close the position early, let it expire, or exercise the option depending on market movements. Fees, commissions, and brokerage approvals also impact an investor’s profitability in options trading.

What Happens During an Options Trade?

Trading options follows a step-by-step process:

- Market Analysis – Traders assess potential opportunities using market data, technical analysis, and economic indicators.

- Strategy Selection – Depending on their outlook, traders decide whether to buy calls, puts, or implement spreads, straddles, or other options strategies.

- Order Placement – Investors specify key contract details such as underlying asset, option type, strike price, expiration, and number of contracts.

- Execution – Orders are matched on an exchange and confirmed in the trader’s brokerage account.

- Position Management – Traders monitor price movements and adjust positions as needed by selling, rolling, or exercising contracts.

- Expiration or Exercise – Contracts either expire worthless (if out of the money) or are exercised (if in the money). Profits or losses are realised based on the final asset price relative to the strike price.

For example, suppose a trader buys Infosys ₹1,500 call options for ₹50 each with a plan to profit if Infosys rises. If Infosys reaches ₹1,600 before expiration, the trader can either sell the option for a profit or exercise it to buy shares at ₹1,500. Conversely, if Infosys stays below ₹1,500, the option expires worthless, and the trader loses the ₹50 premium.

Examples of Options Trading

Buying Call Options on Reliance Industries

- A trader expects Reliance’s stock to rise and purchases 10 call contracts with a ₹2,000 strike price, expiring in three months, at a ₹100 premium per share.

- If Reliance’s stock climbs to ₹2,200, the trader can sell the call options for a profit or exercise them to buy shares at ₹2,000.

- If the stock stays below ₹2,000, the trader loses the ₹100 premium per share paid for the contracts.

Selling Put Options on ICICI Bank

- An investor sells 10 put contracts on ICICI Bank with a ₹500 strike price, expiring in April, collecting a ₹20 per share premium.

- If ICICI Bank’s price stays above ₹500, the puts expire worthless, and the investor keeps the ₹20 per share premium as profit.

- If the stock drops below ₹500, the investor is assigned the stock and must buy it at ₹500 per share.

Call Debit Spread on Tata Motors

- A trader buys a Tata Motors ₹400 call and sells a ₹450 call, both expiring in March.

- If Tata Motors rises above ₹450, the strategy profits, but if it stays below ₹400, both options expire worthless.

- The spread reduces the cost of entry compared to buying a single call outright.

Common Options Trading Strategies

- Long Calls – Buying call options to profit from a rising stock price. Risk is limited to the premium paid, while upside potential is unlimited.

- Long Puts – Buying put options to profit from a falling stock price. A protective hedge for stockholders.

- Covered Calls – Selling calls against owned shares to generate income. Caps upside gains but reduces risk.

- Protective Puts – Buying puts as insurance against declining stock prices. Used to hedge stock holdings.

- Spreads – Using multiple options contracts together, like bull call spreads and bear put spreads, to manage risk and cost.

Other advanced strategies include straddles, strangles, butterflies, iron condors, and collars, which traders use to profit from volatility, directional moves, or generate income.

Is Technical Analysis Needed for Options Trading?

Yes, technical analysis is a crucial tool in options trading. By studying price trends, volume, volatility, and chart patterns, traders can make informed decisions on strike prices, expiration dates, and overall market direction.

Technical indicators such as moving averages, Bollinger Bands, RSI, MACD, and implied volatility help traders:

- Identify entry and exit points

- Measure market sentiment and trends

- Determine the likelihood of options expiring in the money

Although fundamental analysis provides long-term insights, options traders heavily rely on technical analysis due to the short-term nature of most contracts. Successful options trading often combines both approaches to maximise profitability and manage risks effectively.

FAQ About Options Trading Terminology

1. List of options trading terms?

Options Contract, Call Option, Put Option, Strike Price, Expiration Date, Premium, In-the-Money (ITM), Out-of-the-Money (OTM), At-the-Money (ATM).

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered financial, investment, or professional advice. While we strive for accuracy, we do not guarantee the completeness or reliability of the content. Always conduct your own research or consult a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions. MarketUnder.com and its authors are not responsible for any financial losses or decisions made based on this information.

1 thought on “22 Options Trading Terminology For Beginners”